What's The Problem with Meat?

Current levels of global meat consumption are not sustainable. Between 1961 and 2001, worldwide meat production increased by 245%. As the population continues to grow, demand for animal protein may increase as much as 70% by 2050 (24).

In the U.S., we consumed almost double the USDA’s recommended amount of red meat and poultry in 2018––280 grams (~10 ounces) per day, which is over 220 pounds of meat per year (25). Nonetheless, high animal protein consumption is encouraged and incentivized in the U.S.

Our continuing decline in health trends today is in large part due to heavy promotion of excess animal protein consumption. This demand continues to be a function of sustained economic growth and declining retail prices in meat products (25), despite it harming individuals in the long run.

The livestock sector––at every scale, local to global––is negatively impacting the environment by contributing to overuse of freshwater, deforestation, desertification, excretion of polluting nutrients, diverting food for use as feed, inefficient use of energy, and most notably, increased greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (26).

Confined feeding animal operations (CAFOs) emit three main greenhouse gases (GHGs): carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrous oxide (N2O), and methane (CH4) (27). Even though CO2 is widely considered the most harmful GHG, methane (CH4) is 80 times more potent a global warming agent (over a 20-year time frame) than CO2.28 Just one cow can generate up to 500 liters of CH4 per day (27). Thus, CAFOs with cattle alone are estimated to produce 19.5% of all U.S. CH4 emissions (27). As I mentioned last year, GHG emissions are also changing the nutritional composition of our foods. Read more about that here:

The Great Nutrient Collapse: How Climate Change is Affecting Our Food

Climate change is one of the most urgent environmental and humanitarian challenges we face in the 21st century. The scientific literature makes it clear that global food production is one of the largest contributors to this change. Annual temperature data, dating back to the 1880s, remind us that 17 of the 18 hottest years on record have occurred in the 21st century (29,30). We also see a concomitant incidence of daily tidal flooding as a result of sea level rise, which has been accelerating in over 25 Atlantic and Gulf Coast cities (31).

But the question remains: Are all CAFOs bad?

Due to the heterogeneity among agricultural farming practices, the true environmental cost of producing similar goods is highly variable. Information on the environmental impacts of food production are commonly measured via life cycle analyses that assess land, equipment, and other resources needed to grow and raise food.32,33

Therefore, it’s argued that the current heterogeneity among agricultural farming practices creates abundant opportunities to target the small number of farmers that have the biggest impact—with the ultimate aim of implementing substantial mitigation techniques.

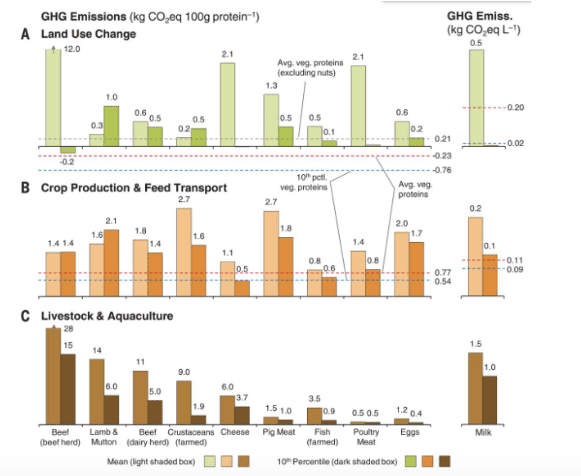

Figure 1. The differences between vegetable and animal GHG emissions will hold well into the future, unless there is a seismic revolution among CAFOs. Note: Emissions from producing feed exceed emissions from producing vegetables. We know that deforestation for animal rearing is dominated by feed, which results in above and below ground carbon losses. Compared to vegetables, animals produce GHG emissions from enteric fermentation, manure, and aquaculture ponds (furthermore, the slaughterhouse effluent adds more GHG emissions). The red dashed lines represent the average vegetable protein emissions; blue dashed lines represent the 10th-percentile emissions; and the dashed gray lines are the 10th-percentile emissions excluding nuts, which are able to sequester carbon if grown on crop and/or pasturelands (34).

Unfortunately, CAFOs are limited by how far they can actually decrease their environmental impact. What is most striking is that even the lowest-impact animal foods exceed the environmental impact of vegetable substitutes (Figure 1) (33).

Dr. Bhandari Is Here to Support Your Health.

As one of nation’s top integrative functional medicine physicians, Dr. Bhandari work with patients suffering from chronic health concerns which modern medicine can only provide side effect-ridden solutions without a cure. By taking the best in Eastern and Western Medicine, Dr. Bhandari understands the root cause of diseases on a cellular level and designs personalized treatment plans which drive positive results. Reach out to SF Advanced Health or call 1-415-506-9393 to learn more.

References

Säll, S., & Gren, M. (2015). Effects of an environmental tax on meat and dairy consumption in Sweden. Food Policy, 55, 41-53.

Jones, K., Haley, M., & Melton, A. (2018). Per Capita Red Meat and Poultry Disappearance: Insights Into Its Steady Growth. Amber Waves, 1-7.

Steinfeld, H., Gerber, P., Wassenaar, T. D., Castel, V., Rosales, M., Rosales, M., & de Haan, C. (2006). Livestock's long shadow: environmental issues and options. Food & Agriculture Org.

Melli, M. (2018). Policy Mechanisms, Precedent, and Authority for State Implementation of Climate Change Agendas. Florida State University Journal of Land Use and Environmental Law, 33(1), 5.

Lovvorn, J. (2017). Climate Change beyond Environmentalism Part II: Near-Term Climate Mitigation in a Post Regulatory Era. Geo. Int'l Envtl. L. Rev., 30, 203.

NOAA National Center for Environmental Information. (2015). State of the climate: global analysis for annual 2015. http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/sotc/global/201513. Accessed 17 November, 2019.

NOAA National Center for Environmental Information. (2017). State of the climate: global analysis for annual 2017. Retrieved from: http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/sotc/global/201713. Accessed 17 November, 2019.

US Global Change Research Program (US GCR), National Climate Assessment, United States. (2017). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Climate science special report: fourth national climate assessment 2017. Retrieved from: https://purl.fdlp.gov/GPO/gpo86261 on 17 November, 2019.

Clark, M. A., Springmann, M., Hill, J., & Tilman, D. (2019). Multiple health and environmental impacts of foods. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Poore, J., & Nemecek, T. (2018). Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science, 360(6392), 987-992.

Elizabeth Grossman, Absent Federal Policy, States Take Lead on Animal Welfare. Civil Eats. (Feb. 15, 2017). Retrieved from: https://civileats.com/2017/02/15/absent-federal-policy-states-take-lead-on-animal-welfare/ on Nov. 21, 2019.

AUTHOR

Dr. Payal Bhandari M.D. is one of U.S.'s top leading integrative functional medical physicians and the founder of SF Advanced Health. She combines the best in Eastern and Western Medicine to understand the root causes of diseases and provide patients with personalized treatment plans that quickly deliver effective results. Dr. Bhandari specializes in cell function to understand how the whole body works. Dr. Bhandari received her Bachelor of Arts degree in biology in 1997 and Doctor of Medicine degree in 2001 from West Virginia University. She the completed her Family Medicine residency in 2004 from the University of Massachusetts and joined a family medicine practice in 2005 which was eventually nationally recognized as San Francisco’s 1st patient-centered medical home. To learn more, go to www.sfadvancedhealth.com.